Just published in the highly regarded journal Nature, researchers analyzing the brain tissues of deceased individuals reported finding a disturbing amount of microplastics widely distributed in the CNS. Extrapolating, they suggested there may be five bottle caps worth, like the ones on a disposable water bottle, that may accumulate in our brains over the lifespan.

Let’s start with a little positivity—when surrounded by so much that is grim, it’s nice to brighten our view and illuminate the good. Geophagia may be good for you. Yes, that’s right, eating a little dirt may be just what we need. But wait, as a bona fide healthcare provider, you cite the standard in the field: the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-V). In this reference to all things that meddle with our minds, the DSM-V is the psychiatric Bible, and it describes geophagia (classified within the broader category of “pica”) as a type of eating disorder.

Now, we are not talking about going out into your backyard and adding scoops of dirt to your breakfast cereal or your evening’s macaroni and cheese, only to note that the body has a way of informing you of a need for something. Geophagia is universal, relatively harmless when practiced appropriately, and may protect humans and animals from certain bad things. Getting a little dirt in your food, or while you or your child gets a little dirt in the mouth during outdoor play, may have beneficial effects like enhancing your immune system, diversifying your gut microbiome, and even providing some helpful skin microbes. A more cautious approach might involve using safe products that are commercially sold. We should be careful not to stigmatize someone who suggests that geophagia is a salubrious dietary adjunct. It’s all about context; they may be right!

Table of Contents

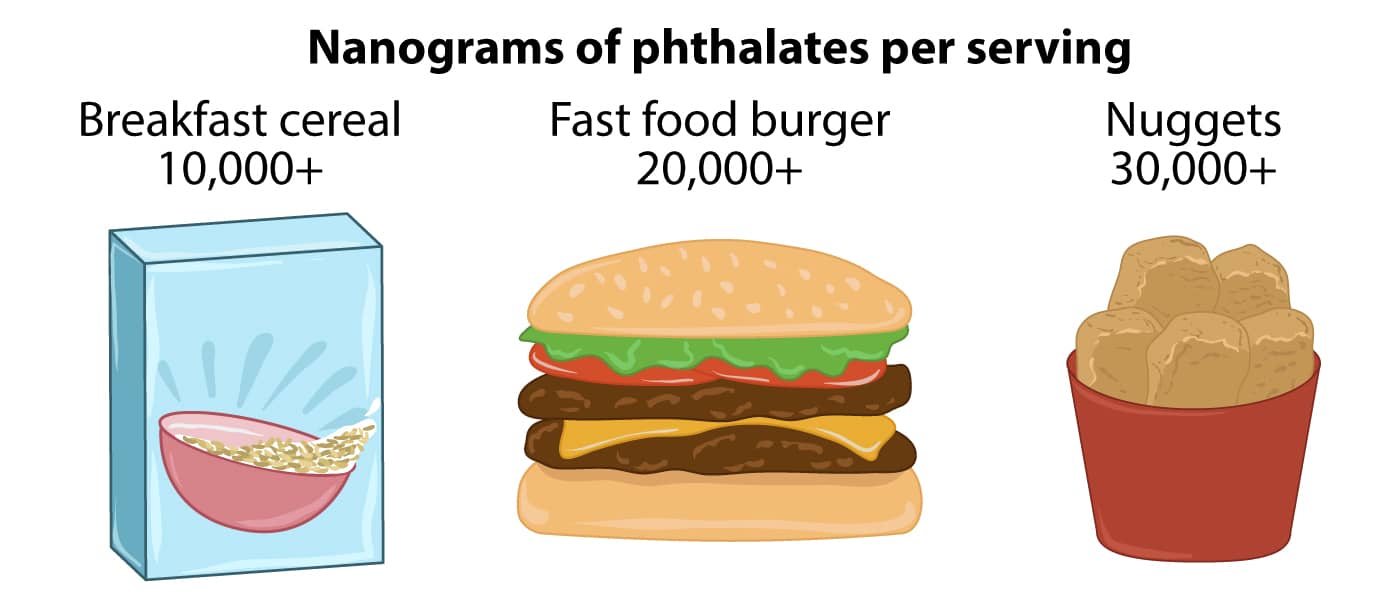

Let’s look at a few areas where these microplastics may be coming from

Vaping

There’s a good chance you’ve never heard of the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labeling of Chemicals, mercifully shortened to GHS. Developed by the United Nations, it establishes and specifies what information should be included on labels of hazardous chemicals and the products that may contain them. The ubiquitous e-cigarette contains over 180 compounds that, when exposed to the high temperature created by the devices, transform into 153 compounds that are considered health hazards and over 200 chemical irritants, as reported in a recent JAMA. It is particularly concerning that long-term use or secondhand exposure to vapor containing these chemicals could lead to a new wave of chronic diseases. These health issues may not become evident until a decade or two later for those who use these products.

The air we breathe

Then there is the issue of the ambient air that all Earthlings breathe. The Environmental Protection Agency established 6 ambient air factors considered health threats: nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, lead, carbon monoxide, particulates, and ozone. Depending on where you live, the outside air can contain a remarkably complex soup of particulates, gases, vapors, and organic and inorganic compounds. These additives largely originate from the combustion of fossil fuels, industrial production of pollutants, and terrestrial fires.

Airborne particulates <100 nanometers (about the size of an average virus) are of particular concern as they can easily traverse our epithelial, endothelial, and neural barriers and penetrate our organs, including the brain. As we noted, their sources are varied, from tobacco smoke, cars, trucks, cooking, cleaning products, plastics of all kinds, fires, and natural and manmade disasters. The latter includes conflict-zone bombs, industrial accidents, and events like the 9/11 attack.

Urban, industrial, and mass transportation corridors may be saturated with ambient air festooned with toxic compounds. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are ubiquitous in our ambient environment and air, many of which are not routinely measured and have implications for global health. It is believed that PAHs are harmful to the developing young brain, are carcinogenic, and negatively affect endocrine function. Breathing polluted air is associated with a host of cognitive impairments and has a strong association with an increased risk of neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.

Based on what we know and the potential and real threats posed, air pollution is a major public health issue. Translational research is needed to inform and generate moderating strategies. We all face varying levels of risk, and compliance with legislation to reduce pollutants is urgently needed.

Plasticization of the human body?

We recently visited an exhibit at our science museum of once-living human bodies and organs that were donated and then plastinated to permit the public to visually explore the intricacies of what lies within each of us. This method deliberately uses compounds to permanently “fix” tissues in a real yet surreal state. This got us thinking about how our diet—and breathing—may be plasticizing ourselves from the inside.

We know that plastics have been injected into every geographic niche on planet Earth—no soil, air, or ocean is plastic-free. Microplastics and nanoplastics—categorized based on size—are pervasive and Machiavellian in their design. They are in the fish in the sea, in the snow and rain falling from the sky, and ride the wind worldwide. Those of you who enjoy a hot cup of tea, steeping those single-use tea bags, release billions of microplastics and nanoplastics into what you are about to drink. Beer, canned soup, salt, fruits and vegetables, bottled water, and emissions from auto and truck tires while driving are all sources of microplastics. Unsurprisingly, there are microplastics in our tap water, well documented in several WHO reports. Plastics are throughout our bodies, not just in our cells and organs, but in our secretions: microplastics are found in breast milk and semen.

Considering the CRNA’s work environment, recent research finds an astounding concentration of microplastics in the ambient OR environment. Most of these come from the unwrapping of single-use, sterile products, surgical drapes, our OR attire, opening drug vials, and many of the myriad activities we engage in daily.

Despite not knowing the health consequences of being awash in an ambient sea of microplastics, as with many issues, we tend to “kick the can down the road” rather than proactively manage it. That said, it just seems prudent that both researchers and clinicians need to get to work on this. For example, shouldn’t we be devising novel methods of packaging the things we use and crafting ways to open them without expelling microplastics into our work environment?

Consider one effort: Verra, a nonprofit that is currently the world’s leading certifier of carbon credits extensively used in the global economy. Verra is now working with the industry to develop high-impact plastics intervention plans to certify them as “plastic neutral” and develop practical alternatives. Humans are complex problem solvers! We can do this!

What about what we eat and drink?

Consuming food and fluids is essential to maintaining life, but there are risks, some of which are potentially fatal. We are familiar with the ever-rising rate of obesity and its close association with certain diseases, but things in our diet carry other risks that we should consider. Many risks are linked to time and culture, one example being where the lack of water free of threatening microbes and contaminants is problematic worldwide and occasionally even in the U.S.

Microbial food contamination is most often related to Salmonella, Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Clostridium perfringens, hepatitis A, or norovirus infections. and though occasionally fatal, their incidence is likely underreported. Abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, vomiting, and fever may commonly occur but are not specifically attributed to a food supplier when a major outbreak occurs (recall Chipotle’s $25 million fine in 2020). The American Medical Association estimates that there are over 48 million foodborne illnesses in the U.S. annually.

Mercury in fish and seafood, pesticides on fruits and vegetables, colorants, flavorings, and preservatives are reported to have adverse consequences. Even the sweetener aspartame is on the radar. The WHO’s cancer research arm, the International Agency for Research on Cancer, labels aspartame as “possibly carcinogenic to humans,” giving it a strength of evidence rating of 2B—the third highest evidence rating out of four levels. And then we are warned that even barbecuing certain foods—steaks, chicken, hot dogs, hamburgers—produces carcinogenic dioxins and nitroso-compounds. Then, of course, there is food contamination with physical contaminants like glass, wood, metal, and insects, to mention just a few.

When recommendations on what to do get confusing

Our trust (or faith) in our government, medical organizations, or industry varies greatly. Medical sources tend to be the most trusted, followed by the government and industry. When different accounts emerge from the three, it can bewilder the consumer and is likely to fuel distrust in all three. A good example is alcohol consumption.

There’s no shortage of alcohol-related research over the years, and the science has evolved. Many believe that light or moderate drinking is healthy based on a 1997 study in the New England Journal of Medicine, whose authors concluded, “In middle-aged and elderly populations, moderate alcohol consumption slightly reduced overall mortality.” Later analysis found great flaws in the study’s conduct and interpretation. At around the same time, the “French Paradox” emerged, linking red wine to lower rates of cardiovascular conditions, primarily due to the polyphenol resveratrol found in wine. This, too, proved a flawed conclusion: resveratrol was found only in sub-clinical amounts in red wine, and none in white wine, and other factors in the French sample accounted for the effect.

The bottom line is that there is no protective effect of alcohol, and there is an elevated risk of cardiovascular conditions of all kinds, hepatic and colon cancers, and neurodegenerative disease with each progressive drink. The medical community remained concerned and skeptical from the start that alcohol is good for your health.

Where does it all leave us in 2025?

We all like to eat, drink, and breathe! Certainly, any ingested substance, by whatever route of administration it is delivered, is potentially harmful. We are reminded of the famous axiom of the Swiss chemist and physician Paracelsus, who, over 700 years ago, penned a foundational principle of toxicology: “All things are poison, and nothing is without poison; only the dose makes a thing not a poison.” We know it today as “the dose makes the poison.”

Be aware and exercise appropriate caution out there! While there are lots of potential toxins out there, live your life not with anxiety but with purposeful mindfulness. Maybe a little less microwaving in those plastic “steamer pouches” for starters?

As CRNAs ourselves, we understand the challenge of fitting CRNA continuing education credits into your busy schedule. When you’re ready, we’re here to help.