Before we get to the possibility of whole eye transplants, the story needs to begin many years ago. Early experiments in organ transplantation, often quite gruesome in their design, began in animals long before the first human kidney transplant in 1939 by the Russian Yurii Voronoy. Like Victor Frankenstein, the protagonist in Shelly’s epic story of a reanimated 8-foot creature cobbled together with organs and tissues of the deceased, Voronoy placed a deceased person’s kidney, hoping for a miracle, into a recipient who died two days later. Then, in 1953, a Parisian mother donated a kidney to her 16-year-old son, the first living human-to-human transplant, which proved only briefly successful.

A milestone was reached in 1954 when Dr. Joseph Murray transplanted the kidney of a brother into his identical twin in Boston, MA. The recipient survived, as did his fully functional transplanted kidney, for eight years until he died of causes unrelated to his relocated organ. Murray was ultimately awarded a Nobel Prize for his pioneering work in the domain of organ transplantation.

It wasn’t until 1962 that genetically unrelated donor-to-recipient transplantation occurred under the protective shielding of immunosuppressive agents. Today, the picture is bright, given the evolution of immunosuppressive agents, surgical techniques, anesthetic advances, and careful matching of the donor-recipient using national databases and artificial intelligence tools. The most recent data reveals a 5-year organ and patient survival rate of 80% for kidney and liver transplants. Survival for decades is not uncommon. Today, organ transplants of many different organs are performed routinely and with enormous success.

When need and human ingenuity intersected

In 2005, a woman in France was severely disfigured by a dog attack, and surgeons restored her face using a transplanted nose and mouth from a recently deceased donor—demonstrating the potential for both aesthetic and functional recovery in extremely complex procedures. Ethical considerations, rejection potential, quality of life issues, and cost were aggressively discussed in the literature and at national conferences. The patient lived for 11 years, eventually succumbing to lung cancer.

As with Murray’s success with the kidney, this first partial face transplant catalyzed international interest. A 2024 paper in JAMA, reported that 50 face transplants have been performed, or at least formally reported, in 18 academic surgical centers from 11 countries worldwide. As of this writing, the transplants include 39 men and 9 women, the majority having experienced a life-threatening trauma where options for restoration were either not working out as hoped or simply unavailable. One patient’s transplant failed and the procedure was repeated, thus bringing the total to 50 actual transplantations. Marshaled on by human ingenuity and technological advances, whole face transplantation evolved with bone reconstruction and innovations in facial surface treatments. Like outcomes with kidney and liver procedures, the report in JAMA cites survival rates for 5- and 10-year facial transplantation of 85 and 74%, respectively.

Transplantation of an entire eye?

Complete loss of the eye can result from catastrophic injury or severe pathophysiological conditions. For a long time, the immense anatomical and physiological challenges associated with whole-eye transplantation have discouraged serious consideration of the procedure. A formal consensus statement by the U.S. National Eye Institute Advisory Council in 1978 read that “… any effort to transplant a mammalian eye is doomed to failure…” citing the cutting of nerves, trauma to axons, inability to ensure blood flow, and immune system issues.

Undeterred by even the most knowledgeable skeptics, researchers have now reported a truly astonishing procedure in a recent JAMA article. With an enormous amount of research, innovation, and preparation leading up to the procedure, a team of clinicians from ophthalmology, radiology, plastic surgery, and anesthesiology at New York University performed a 21-hour surgery, implementing innovations not previously employed in a living person.

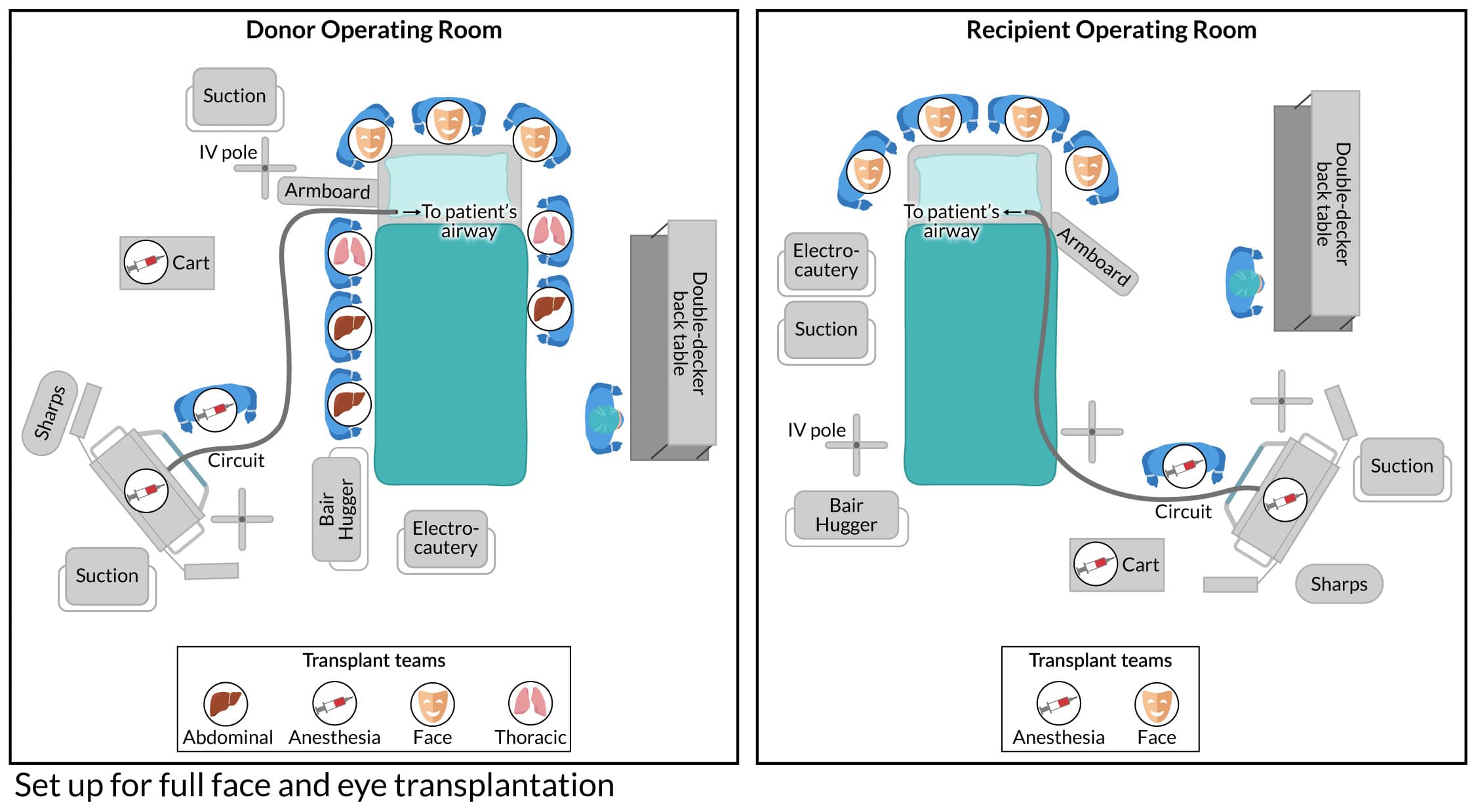

Microsurgical techniques and instrumentation, along with stem cells injected into the optic nerve, resulted in a combined nearly full-face and eye transplant in a victim of a catastrophic high-voltage electrical injury. Over a year later, his face has maintained remarkable form and function, and the eye, while not restoring vision, maintained its baseline geometry, normal intraocular pressure, blood supply, and some retinal structure. Evoked potentials and functional MRI studies demonstrate some response of the retina and the visual cortex to light but not the ability of the brain to perceive it. The figure shows a “drone view” of the operative infrastructure, harvested from a deceased donor whose tissues were kept viable.

The challenges in whole eye transplantation are extraordinary, and this case represents a truly monumental first step, demonstrating a potential pathway for future restoration. The JAMA report of an entire eye being transplanted with a nearly full facial transplant reveals that allograft survival of a whole eye without rejection, and with some evidence of the retina responding to light, is promising. The anesthetic care challenges involved in such a procedure are prodigious and are chronicled in detail by those involved in the case. CRNAs involved in such cases provide care that spans all the perioperative phases and play an enormously important role in optimizing the procedure’s chances of achieving a favorable outcome.

The renowned poet Robert Frost penned his beautiful poem, Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening, where he metaphorically speaks to life, death, the tug between optimism and pessimism, and the journey of life that we all deal with. In the final stanza of his poem, he wrote,

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

CRNAs care for patients, often at the most difficult and stressful times in their patients’ lives. We become part of their life’s journey and, in that role, assume a promise to provide exquisite and humanistic care that can prove challenging, if not downright daunting. It’s what we do, offering hope and promise to those we care for, even if that journey ahead is long, dark, and deep.

As CRNAs ourselves, we understand the challenge of fitting CRNA continuing education credits into your busy schedule. When you’re ready, we’re here to help.